What can the Switch 2 and the Playdate tell us about the lifecycles of game consoles?

Nintendo released the Switch 2 on June 5th of this year and it is, in almost every measurable way, an improvement over its predecessor. Its built-in screen is 1080p rather than 720p, and when docked it can output images at 4K. It has a maximum frame rate of one hundred twenty frames per second, whereas the older model topped out at sixty. It has two hundred fifty-six gigabytes of built-in storage instead of thirty-two, twelve gigabytes of RAM instead of four, two USB-C ports instead of one, and WiFi 6 instead of WiFi 5. Almost every number that can be used to describe this device is bigger than it was before, except for battery life, which may run a bit shorter: it’s possible that took a hit to power all of these new technologies.

But aside from that, it is everything the original Switch was, except more powerful, more capable, and more modern. That is why the Switch 2 exists. And eventually, that is also what will kill it.

Why Do Game Consoles Die?

The release of the Switch 2 did not immediately kill its predecessor. Indeed, the original Switch is still being sold: not only is it likely to become Nintendo’s best-selling console, but it also just got a price increase, which is unheard-of for game system in its ninth year and uncharacteristic of a console that will soon be phased out. The Switch 1 isn’t dead yet, and it will likely continue to be sold for the foreseeable future. But if we look at Nintendo’s history, we can reasonably guess that the Switch 1 is living on borrowed time.

The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was released in Japan in 1983 (known there as the “Famicom”), and its successor, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, was released in 1990. That release did not signal an immediate end for the NES: units continued to be produced for the worldwide market through 1995, and it received its final official game that same year. This was the start of a cycle: the SNES was itself succeeded by the Nintendo 64 in 1996, which was replaced by the GameCube in 2001, which gave way to the Wii in 2006, which was supplanted by the Wii U in 2012. For the most part, the older consoles overlapped with their successors for some time, with the exception of the low-selling Wii U, which halted production months before the Switch released in 2017. But inevitably, each older console stopped being manufactured, its games stopped being sold, and its online services supporting multiplayer and digital storefronts were shut down as all eyes turned toward the new. This most recently occurred in 2023, when Nintendo stopped allowing new digital purchases on the Wii U and 3DS eShop. On Nintendo’s support page for the eShop’s discontinuation, they explained this occurrence as a consequence of a product line’s “natural lifecycle.” The Wii U and 3DS lived, and so they must also die.

Nintendo is not alone in using the language of life, death, and time to describe consumer electronics, and this language is reflected across the industry and hobby. We talk about console releases in terms of “generations” because we view them as an inevitable linear succession, with each “next generation” device replacing its forebear. We’re excited when these newer devices work with our older games (not guaranteed!), and we call that “backward compatibility,” describing how a technology that’s supposed to always point forward into the future occasionally allows us to look back at the past. But when Nintendo uses a phrase like “natural lifecycle,” it implies that the decision to close the eShop, along with access to many games exclusive to that service, is not a decision at all. This is merely time marching on, allowing new generations to fall into place as they always do and always should. Time is inescapable, as is progress, as is death.

But what does it mean for consumer electronics to die? There are multiple factors, and one of them is access. For instance, I keep a collection of older consoles and games, and I still use my Wii U and 3DS to revisit past titles like Metroid Prime Pinball and Wii Sports Resort. But old systems aren’t just for replaying the familiar: at other times, I’ll finally dive into a game that I had purchased but never gotten around to, as was the case a few years ago with Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors. And I’m not alone in enjoying older games, as retro handhelds have seen a recent resurgence. Good game design ages gracefully, and when old systems are taken care of, they can still boot up and run just as well as new ones. However, if they’re no longer manufactured, they’re much harder for the public to access, and that access depends on the supplies in the used market. They’re also less feasible to repair: I once recycled an older DS Lite after an impact damaged its shoulder button and chassis, and it’s not like Nintendo ever made those very user-repairable to begin with.

If it’s difficult to access a game system no longer being manufactured, it’s often even more difficult to access that system’s library of games. The shutting down of storefronts and servers supporting a given system is a factor in this, but it’s not the only one. There are also games that were designed for a system’s unique hardware, like the aforementioned Metroid Prime Pinball which relies on the DS and 3DS’s unique, vertically aligned dual screens to render a full pinball table, making it difficult to port to newer hardware. Other times it’s just a lack of interest on the developer or publisher’s side in doing the work necessary to port older games to newer hardware even if they would be suitable, leaving games locked to the systems they were originally designed for. Further, games released on physical cartridges or disks are subject to the same risks of damage and decay as their systems: once they stop being manufactured, we will have ever-diminishing copies available in the world. This is one of the many reasons that games preservation is a tough field, and we’ve already lost many classic games as a result.

It’s tempting to think that gaming on more open platforms such as PCs and mobile phones is the answer, and there’s some virtue to this, but these platforms face their own challenges in preserving games. PCs and mobile phones are built on a series of constantly-evolving standards and specifications that often make older games non-functional. For instance, iOS, which is only recently became even remotely more “open” than game consoles, lost support for 32-bit games in 2017. Similarly, games released for PCs running an OS before Windows 7 are generally unplayable on modern systems, including my copy of Bionic Commando Rearmed which refuses to run on my Windows 10 PC. MacOS is losing most of its Rosetta translation layer in 2027, ending its compatibility with programs designed for the x86 chip architecture; there’s a carve-out for some games in that loss, but who knows how long that will last, and how many games that will cover? Even if developers want to keep offering their games on these various platforms and storefronts, the platforms themselves are always changing: what runs on today’s version of Windows or MacOS may not run on tomorrow’s.

I prefer playing games on consoles in part because their stable base of technology makes game compatibility far more clear: so long as my 3DS works, it will always be able to play any game made for the 3DS. Meanwhile, my iPhone XR struggled to run the more recent Sonic Dream Team even though the App Store rated my phone as compatible with the title. It worked, technically, but it stuttered and chugged and just wasn’t pleasant to play. Further, playing on consoles brings the benefit of what they can’t do: my Switch will never beep or chime to let me know I have a new text message or email, making it easier to disconnect while playing on a console rather than a general purpose device. But regardless of whether you play games on consoles, mobile, or PC, they’re all caught up in the “inevitable” cycle of progress, of losing support when that support no longer benefits the manufacturer’s interests. This fall, both my phone and my PC will become ineligible for further security updates, despite the fact that they both serve my needs just fine: my “choice” is to upgrade or to live with increased risk. And with game consoles, as hardware gets discontinued and services get shuttered, the “choice” is to upgrade, or stop playing new titles entirely.

Consumers and players are not the ones with meaningful choice here: platform holders are, and their choices are driven by business interests rather than the inevitable march of time. It’s reasonable that companies like Nintendo, Apple, Microsoft, and Sony should be under no obligation to continue supporting old hardware and software, an effort that costs money, labor, and other resources. But they also choose to design their systems to only function and thrive with their exclusive support. When Apple and Microsoft decline to continue supporting older devices with security and OS updates, they don’t make it possible for other entities to do the same in their place. And when Nintendo, Microsoft, and Sony shut down online services and options for new games on older consoles, they don’t open the door for others to step in, and it is in fact illegal for others to make the attempt. Even if you wanted to release a new game for an older system like the 3DS, Xbox 360, or PlayStation 3, you can’t unless the given platform holder approves it, and they have more financial incentive in promoting the new.

Consoles don’t die because they reach the end of a “natural lifecycle.” They die because it suits the business needs of their manufacturers. Consoles die when they’re no longer being manufactured, when new games can no longer be developed for them, and when the services that support the access and use of their games are shut off. These older devices can still be explored, and I encourage doing so if you’re able. But when I think of this, the word “archaeology” springs to mind. It’s embarrassing to think of technologies and media that are only a few years or decades old as “ancient,” but what other term describes the exploration of a space where a lifecycle has already occurred, and where new growth is impossible? But this kind of archeology is actually the best-case scenario, as many unsupported consoles will inevitably make their way to the dump in the form of e-waste. The churn of technology and progress isn’t just an issue of game access and cultural preservation, it’s a detriment to our environment as well.

The new Nintendo Switch 2 costs four hundred fifty dollars, making it Nintendo’s most expensive console yet. But real cost isn’t just the price in dollars: it’s that price, plus the losses we as a society incur in terms of lost games, lost culture, and environmental impact. I don’t say this to discourage people from buying new technologies and game consoles: as I’ve said, consumers are not the ones with meaningful decision-making power, and these issues are better addressed through legislation and societal investments in recycling and preservation than in individual consumer purchase decisions. Instead, I raise these issues to contextualize the costs we pay not only when we buy new consoles, but when companies choose to release them in the first place.

Nintendo released the Switch 2 on June 5th of this year and it is, in almost every measurable way, an improvement over its predecessor. But what does that actually bring us? And is it worth the cost?

Why Are Game Consoles Born?

New game consoles are born to make money for their manufacturers: it is good business to sell your audience new hardware. Obvious, right? But “we want to make money” doesn’t make for inspiring ad copy, and is often not the reason we’re given when a manufacturer shares the good news of a new console’s birth.

To hear it from Microsoft in 2019, their Xbox Series consoles would “power your dreams.” In announcing the PlayStation 5, Sony declared that “play has no limits.” But then I suppose they found some limits, so they released the PS5 Pro which “unleashed” play. Nintendo was more grounded when announcing the Switch 2, saying the new system would provide “powerful new hardware, reimagined online capabilities, and a broad range of games.” But what does this all mean? What are we actually getting when a console manufacturer sells us a new box with bigger numbers on it? Games that weren’t possible before on the hardware we already own? Or the same games, with more polygons?

In The Art of Game Design, Jesse Schell makes a distinction between “foundational technology” and “decorational technology,” and that distinction is useful here. Foundational technology is technology that makes an experience possible: when Nintendo released the DS in 2004, that system introduced a touchscreen that served as the foundation for games like WarioWare: Touched!, Meteos, and Trauma Center: Under the Knife. These games made extensive use of that touchscreen, and would not have been possible without it; furthermore, WarioWare even made use of more esoteric system functions like the DS’s microphone. Meanwhile, decorational technology is technology that isn’t needed for an experience to be possible, but it can make that experience better: when Nintendo releases remasters of older games for new platforms, such as Luigi’s Mansion 2 HD or Super Mario RPG for the Switch, these re-releases are almost exclusively benefiting from technological improvements as decoration: they may look sharper and run more smoothly, but the latest technology was not necessary for these games to be possible. Indeed, Luigi’s Mansion 2 was originally released in 2013, and Super Mario RPG premiered in the nineties.

What makes the Switch 2 stand out in the history of Nintendo console releases is the conspicuous absence of technologies that seem obviously foundational for new kinds of games. When the Nintendo 64 succeeded the SNES, it did so while introducing 3D graphics and an analogue stick more suited for control in 3D spaces than the traditional d-pad. And as I said previously, the DS pioneered touchscreen games, and the Wii did the same for motion controls. Even in the 2010s, Nintendo kept making bets on distinctive technologies like glasses-less stereoscopic 3D for the 3DS and tablet-connected games for the Wii U. Both of these innovations failed to make a case for themselves as foundational and were abandoned in subsequent hardware releases, but it showed a company that was still pushing for new kinds of technologies in games, rather than iterative improvements to existing processors and other internal specs. But the Switch 2 mostly bucks this trend. It includes new features like the Joy-Con’s “mouse mode” and the camera-integrated GameChat, but it’s difficult to imagine these features as being foundational for lots of new games. As others have noted, the Switch 2 mostly feels distinct from the Switch as a spec-bump upgrade, and lacks the big swings Nintendo has long been famous for. Its identity is “the Switch, but more modern.” But is that the same as lacking new foundational technologies?

The tricky thing about the “foundational” and “decorational” framework is that no technology is purely foundational or decorative on its own: what matters is how often these technologies can be used in games that take advantage of them, and how those games use them. And while the debut of some technologies like touchscreens and motion controls more obviously lent themselves to new kinds of play, that doesn’t mean iterative improvements to internals can’t also be foundational. Mobile phones pioneered the yearly spec-bump upgrade, and as a result we have games like Pokémon Go, which rely on interconnectivity and the quick processing of GPS data not possible on the original iPhone. As for consoles, I played Ratchet & Clank: Rift Apart on a borrowed PS5 a few years ago, a game that features its protagonist using dimensional rifts to shift seamlessly between spaces and environments. The developers have said that this gameplay was made possible by the faster read/write speeds on the new console’s SSD, and could not have been done without the iterative improvement to that technology.

It’s also worth mentioning that the novel technologies Nintendo has been historically famous for are also neither purely foundational or decorative: they can make new forms of play more likely, but it’s not guaranteed. The Wii’s motion controls were foundational to Wii Sports, where swinging the Wii Remote could simulate the motions of tennis or golf: if you take out the motion controls, you have a totally different game. However, that same technology often felt shoehorned into other titles in the form of “waggle,” or using a shake of the remote for an action that could have just as easily been mapped to a button press; in other words, “waggle” is a decorative use of motion controls. This was the case for Nintendo’s other Wii launch title, The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess, where shaking the remote swung an in-game sword, but the actual motion of the sword seldom reflected the motion of the remote. It’s telling that the same game saw release on both the GameCube and the Wii U without motion controls, and the experience was relatively unchanged.

Now, why does all of this matter? I bring up distinctions in foundational and decorational technologies because they help us understand what we’re buying when we buy a new console: the new console’s technology will provide a foundation for some new kinds of play that were previously not possible, while other new titles that would have been possible on older systems will benefit from new technologies as decoration. And while I place more value on the former, I don’t begrudge the latter. One of my most-played games on Switch is Super Smash Bros. Ultimate, the latest in a series of games which has not seen a radical, foundational change since its Melee iteration on the GameCube in 2001. But it now has a bigger cast, more stages, looks sharper, and has had its design honed and iterated upon over the course of two decades. It is the definition of a game built on a series of design refinements and visual improvements, and I honestly love it. But there are signs that even these iterative, less-ambitious games will soon be in short supply.

As Stephen Totilo of GameFile has reported, Nintendo’s count of annual game releases has diminished steadily over the last few years, despite convening its teams that once made games for both home consoles and portables to focus their work on a single, combined platform. This diminishment is not exclusive to Nintendo and is actually true of all major publishers, and a core reason for this lies in the ever-evolving specs of modern technology itself. The cost in time, money, people, and resources to make titles that take advantage of advances in graphical and computational complexity has skyrocketed, resulting in fewer big-budget games that can accurately be said to use all of this new technology as either foundation or decoration. That’s not to say that we’re getting fewer games overall: the number of games released annually has also risen. What has shrunk is the number of games that can make use of all the extra hardware muscle in any meaningful capacity. Many popular games run just fine on older hardware: GameFile also reports that the highly anticipated Hades 2 runs at sixty frames per second on both the Switch 2 and the Switch 1. And Balatro, one of the most popular titles of last year, can run on just about anything.

Where we earlier explored “cost,” we can now examine “worth”: what do you get for what you pay, and what are the positives that a new console brings? I believe that the worth of a game console shouldn’t be considered in terms of all the games we will play on it, but in terms of the games we play on it that benefit from the hardware’s improvements and innovations over that of its predecessor. And if we’re getting fewer games that do benefit from the hardware in either a foundational or decorational sense, at what point do we say that the worth of new consoles no longer outweighs the cost? And how much weight would our determination even have when, as I’ve said, the choice is so often made for us? Upgrade, or stop playing. Upgrade, or get out.

As I was writing this piece, I got an email from Nintendo saying it was my “turn” to buy a Switch 2. Months ago, I signed up to be notified when I could access Nintendo’s preorder system, and now I can, two months after the console’s release. I’d normally wait: I still have plenty of games I’m playing on my current Switch and, let’s face it, the last game I reviewed released twenty-seven years ago, I don’t exactly keep up with the cutting edge. But we elected a president who loves to start pointless trade wars, and the Switch 2’s accessory prices already went up after he announced a series of tariffs in April, as did the price of the five year old Xbox Series consoles. Unlike most of its predecessors, the Switch 2 will likely be cheapest at launch, with a financial penalty for anyone who chooses to wait. So I bought one.

I don’t have it yet, but I expect to enjoy it. I buy Nintendo hardware because, despite what their reliance on long-running franchises would imply, I think they make the most consistently innovative big-budget games of any company, regardless of whichever technologies are currently in their focus. Super Mario Odyssey and The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild were both fascinating explorations of open-world play. Echoes of Wisdom could have been just another top-down Zelda title, but instead created a unique way of engaging with a classic Hyrule setting. Splatoon, which I missed on the Wii U, is a fantastic shooter that stands apart thanks to unique movement and coverage mechanics made possible by abandoning realism in exchange for absurdity. ARMS is an oddball take on the fighting game genre that does well both competitively and at parties. And even when Nintendo isn’t innovating, its polish on games like Super Smash Bros. Ultimate often feels well worth the cost. As for the new stuff, Donkey Kong Bananza looks terrific, and Mario Kart World looks like a fun game for social nights. I’m excited to try Drag x Drive, which looks to be a rarely foundational application of the Joy-Con’s new mouse mode, and I’m curious to see why Masahiro Sakurai chose now to revisit Kirby Air Rider. Lastly, I appreciate that this new Switch is (mostly) backward compatible with the original system’s games .

But in releasing a new Switch that focuses on improving internal specs and on being more “modern” rather than trying something genuinely different, Nintendo has released a console that invites its own eventual obsolescence. Chips can always get faster, and graphics can always have a few more polygons: nothing ages so quickly as “modern.” With their previous hardware releases, we were always able to wonder “what next?” If Nintendo continues to release similarly incremental upgrades to its Switch line, as Microsoft and Sony have long done with their own consoles, we will instead just be asking “when?” All the while, fewer developers will actually be able to take advantage of these improved capabilities. The console cycle will repeat indefinitely so fewer and fewer games can live, while we lose access to more history. Modernity gives, but it also kills as it strives ever forward with no destination in sight. We see this forward march as inevitable, inseparable from the march of time.

But this kind of progress is not inevitable: it is always a choice. Nintendo has previously chosen to take bets on new and risky technologies, and now it is choosing otherwise. There will be benefits to this: like Ratchet & Clank before it, Donkey Kong Bananza is said to take advantage of the system’s new internals in a way that made the game struggle when it was initially in development for the Switch 1. The Switch 2’s technology is indeed a prerequisite for this game’s existence, but that doesn’t mean we would have no game without it. Part of creativity is designing within constraints: what would Bananza be like if the extra hardware wasn’t an option? What kind of game would we have gotten if it released on the Switch 1, if the developers needed to pivot to a gameplay system feasible on the older device? Technology makes new kinds of games possible, but that doesn’t mean existing technology is ever exhausted of possibility: in 2024, both Arco and Animal Well brought us novel gameplay without needing advanced tech in order to run.

We think we advance technology to make new games possible, but how often do we actually design games to justify the tech? Can we instead design games within limitations, to make the most of what we already have? Or will we forever be upgrading, for the sake of increasingly fewer games, at the cost of our history and our environment?

To choose to be “modern” is to choose a limited lifecycle, and to choose obsolescence at next year’s bigger number. But what would happen if a console did not root its identity in “modern?” What would its “natural lifecycle” be?

The Console Born Old

Software company Panic Inc. released their first piece of hardware, the Playdate handheld game console, in April 2022. It was released to generally positive reception, paired with some bafflement about its price: this was an obviously limited, low-power, retro-style console with a launch price of one hundred eighty dollars, which was only twenty dollars short of the easily more capable Switch Lite (both system’s prices have since increased). How does that make sense? How could it survive? But three years later, it’s not dead yet; Playdates are still being sold, and games are still being made and released for the platform. But how much longer could it last?

What makes the Playdate so odd (aside from its similarity, in size and appearance, to a slice of cheese) is its conspicuous lack of modern technologies. It has sixteen megabytes of RAM, while the Switch 2 has seven hundred fifty times that amount. Its screen resolution is four hundred pixels by two hundred forty, making for a pixel count roughly one eighty-sixth that of the Switch 2’s maximum output. That screen is one-bit, with each pixel displaying only black or white with no shades of gray; meanwhile, the Switch 2 is capable of emitting colors in the HDR range, and even the original Game Boy could generate four different shades of gray-green. And it’s not just processors and screens: the Playdate has lost a number of the analogue sticks, triggers, bumpers and face buttons now standard to the modern gaming controller, reducing down to a single D-Pad, two face buttons, a system lock button, and a menu button that pauses the game. There’s also an accelerometer for detecting movement and tilt, though in my experience it’s not used much. Oh, and there’s a crank on the side: it pops out of a storage nook, and you can turn it. How’s that for innovation?

But in the absence of modernity, distinct advantages have been found, and some have even been regained. Without having to house a beefy processor, GPU, or fan, the Playdate is supremely pocketable, and is less than half the size of my phone. This has not been true for any other dedicated game console since the 3DS or the PS Vita; in other words, we haven’t had pocketable consoles since smartphones became ubiquitous. And while smartphone gaming threatens to drain the battery of the same device you need for business and emergencies, the Playdate’s exclusive focus on games avoids this pitfall, and its battery lasts for hours of play and days of rest: in my usage, it’s only had to touch base with its wall charger once or twice a week.

Another standout feature for the Playdate is its screen. Despite having a low pixel count, it’s remarkably sharp, lacking any of the Game Boy’s fuzziness, and its high refresh rate makes animations smooth. The black and white limitation becomes attractive, as grays and tones are rendered in dithering and shifting patterns of black and white. The screen is also reflective, making it lovely in direct sunlight, whereas even my Switch OLED can’t make most games pleasant to play outside. Post-pandemic, I’m looking for more opportunities to spend time outdoors and I appreciate a game console that doesn’t confine my hobbies to ceilings and walls. I’ve seen many lament the lack of a backlight, and there’s some truth to that: because the Playdate doesn’t illuminate its own screen, you are limited to playing in spaces with ample light. But with more and more of modern life situated in front of bright screens, it feels easier on my eyes to play on a device that doesn’t beam any more light at my face than I already get. When I’m not playing outdoors or on the go, I play under the same lamp I use for reading books, and it feels just as peaceful.

Don’t get me wrong: by embracing technological limitations, the Playdate does, in fact, have limits. Obviously, anything involving color is a no-go, as are many forms of 3D gameplay, not that it’s stopped some developers from trying. Multiplayer is mostly absent: as of this writing, there’s no networking capability between devices, and I haven’t personally seen games implement any kind of pass-and-play. The Playdate, so far, is a solo-play device, more akin to an e-reader than a networked console or a Switch with pop-off Joy-Cons. You won’t see swarms of Playdate users playing together in the park, as I do with people still playing Pokémon Go on their phones nine years after that title’s debut.

The Playdate cannot do everything. But neither can more “modern” systems, because technological progress rarely manifests as strict improvement, and is more often a form of exchange. In transitioning from the 3DS to the Switch, Nintendo’s flagship gaming platform lost easy portability when it traded away pocketability for a bigger screen. It also lost StreetPass and “Download Play” multiplayer, with the latter only recently revived on the Switch 2 in the form of “GameShare” streaming. And all of this is on top of the previously discussed trade-offs in game compatibility, along with losses in accessory compatibility and other system-unique features.

I wouldn’t want the Playdate to be my only console; after all, I bought that Switch 2 for a reason. I like 3D games, I like big-budget titles, and I like colors. But I also wouldn’t want the Switch 2 to be my only console: despite being a handheld, it’s size, bigger than even the original switch, means it will have an even tougher time competing for space in my bag with my other belongings. And if it’s anything like the original, it still won’t play well outdoors. In pursuing the modern, it’s lost advantages that even the original Game Boy had locked down.

But because modernity is not central to the Playdate’s identity, its future is not foreordained. By not being built to the latest technological standards, the Playdate doesn’t invite obvious calls for a sequel or upgrade. It doesn’t make sense for a Playdate 2 to have a higher-resolution screen, or a more advanced processor: if any of those were important to the Playdate’s identity, it would already have them. Because that identity isn’t rooted in modernity, there’s no expectation for how long this console should last or how long it will continue to be produced. If I had to design an upgraded Playdate, I’d make it more repairable, but with no other changes.

And there are advantages to that stability, too: unlike ever-evolving platforms like mobile and PC, a console’s stable base of technology means that, hypothetically, a game designed for the Playdate today could run as well as, and alongside, a game designed for the Playdate decades from now. And because the Playdate is an open platform that supports sideloading, it’s more than possible that games could continue to be made for the system far into the future, even if Panic were to withdraw their support for the platform as Nintendo did with the 3DS and Wii U.

Now, will people actually be developing games for the Playdate in future years and decades? That’s impossible to say, but I have reason to be optimistic. There is a sense in which more restricted game consoles can be likened to different mediums in the visual arts. The 1998 movie Mulan doesn’t look inherently worse than 2013’s Frozen, despite the latter’s animation being made with “more advanced” 3D technologies as opposed to the former’s hand-drawn artwork. Similarly, Japanese manga comics don’t look inherently inferior to Western superhero comics, despite the fact that the latter most often uses color while the former is more commonly rendered in black and white. None of these mediums are inherently better or worse than the others. 3D animation is not better than 2D animation for being more “advanced.” Color comics are not superior to black and white comics for being less “limited.” Instead, art is remarkable and stirring in relation to its medium’s limitations and the artist’s proficiency with their chosen tools; all mediums are capable of both great works and mediocrity.

I believe that certain game consoles lend themselves to becoming “mediums” in the same way that other mediums are defined by their tools, such as the ink pen or the 3D graphics program. And tools are defined by their limits as much as their capabilities: the ink pen is capable of dark blacks, and limited to thin lines and marks as opposed to textured brush strokes. The capabilities and limitations both make the medium recognizable to the audience: we don’t wish a skilled ink drawing was an oil painting, and instead focus on how the artist used the medium, and how the finished piece does or doesn’t move us.

Similarly, it’s telling that we laud modern games that emulate, realistically or not, the limitations of older platforms, such as Shovel Knight and the NES or Mouthwashing and the original PlayStation, without lamenting their lack of advanced graphics: we recognize the limitation the artist is working with, and admire their proficiency with the form. Morphcat Games even went a step further, developing the modern Micro Mages to actually run on the original NES while optimizing the game’s capabilities through wise use of the technology. These visuals aren’t “worse” than those of games using advanced 3D graphics: to me, they read as different visual mediums that don’t elicit an apples-to-apples comparison. The limitations of those platforms lend a sense of character and human workmanship to their games, and it’s not surprising to me that developers often seek to emulate those limits on modern hardware. We even have tools like GB Studio that allow developers to make games within the limitations of the original Game Boy, but while running on today’s technology.

Do you think the same will ever be true of a tool meant to emulate the limitations of the Switch 2, the PlayStation 5, or the Xbox Series X? I doubt it; “advanced 3D graphics” has its own unique appeal and is a medium unto itself, but it’s a medium not grounded by a limit. Instead, it’s a medium where growth is defined as always needing to exceed its previous limits, always needing newer technologies to advance its bleeding edge. Modern game consoles lack an identity defined by strict limits, and thus invite their own obsolescence at the hands of their successors: in other words, no modern console is likely to ever become it’s own distinct, lasting medium. But the Playdate, with its strict limitations, has a character and charm all its own. The Playdate’s limitations stamp its games with the mark of a specific, defined medium, and mediums invite mastery. And this isn’t just a platform for coders, as Panic has released an entry-level tool for developing Playdate games as well. While not certain, it’s more than possible the Playdate will continue to attract development at all levels for years to come, and that we’ll see advancements not in how the system is physically upgraded, but in how it’s utilized by developers who become more skilled in this space.

By choosing limits, the Playdate could potentially live far longer than its more advanced peers. But “longer” isn’t “forever,” and none of this means the Playdate is immune to the passage of time. It will die one day, as all things do. Units will stop being manufactured, and they’ll be harder to track down. They’ll break. They’ll get lost. They’ll end up in the dump. And games will only be made in relation to an audience’s engagement with them: any discontinuation of the hardware is likely to result in fewer players, which reduces potential revenue for new games, which discourages development of any new games at all. But because the Playdate isn’t tied to our default idea of progress, we don’t know when that date will be. It could be soon, or it could be far off in the future. We’ve never had a console that stood so far outside of modernity, and so we don’t have a comparable frame of reference. A console has never been made on such stable ground.

Unlike other consoles, there is nothing about the Playdate’s birth that determines its time of death. So what will it do in the meantime?

You’re Alive, Playdate. Now What?

If I’m going to spend so much time talking about the future potential of the Playdate, it’s also worth mentioning what it’s like to use now. As I’ve said, I appreciate its portability, its sun-friendly screen, and its capable battery life. But how are the games? And where do you find them?

Because of the Playdate’s open nature, you can find many games on Itch made by independent developers. And it mostly is independent developers and small teams: because the Playdate simply isn’t capable of the complex worlds and high-end graphics that eat up much of a modern game’s budget, it’s well suited for smaller projects. Many of these games can also be found in the Catalogue, Panic’s official Playdate store. It seems well supported: I get a notification on the device most weeks to let me know new games have been added to the Catalogue. I’ve purchased a few, as well.

However, even before the Catalogue’s launch, Playdate had a novel system for introducing new players to the console: a “season” of twenty-four games, delivered two per week to your Playdate starting when you first power up the device. This season includes both great games and clunkers, as with all game libraries, and they speak to the breadth and possibilities available on even such limited technologies. Since that original release three years ago, Playdate has released a second season of games that concluded in recent weeks. I’ll be covering those here on the site soon, but for now I’d like to talk about some of those original Season One games. I only got my Playdate this year, so they’re still new to me. These are some of my favorites.

Casual Birder

Developed by Diego Garcia.

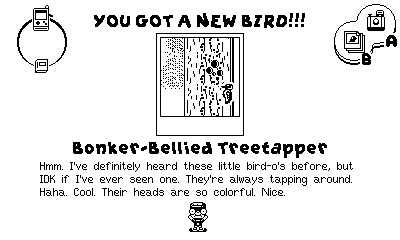

What is the connection between knowing something and loving it? In Casual Birder, you play as an irredeemable dork with a very faint knowledge of birds, but you also totally love them. Will your lack of knowledge prevent you from winning the local bird photography contest? The only way to find out is to point your camera, snap pics, and collect them in your journal where you give them names like “Dirty-Domed Hunkadoo” and “Junkbird.” You would think passion leads to wisdom, but perhaps the real wisdom is just taking joy in the act.

This is an adventure game, where you split your time between photography and solving narrative puzzles. The photography is curious: many birds are just a few pixels, not always identifiable as a bird in stillness, but made alive through motion and sound. A woodpecker (sorry, a “Bonker-Bellied Treetapper”) is identified through its characteristic hammering sound, and the way it flits among trees covered in holes. A “Missile Thrump” darts around the screen, never staying in the same place for long. To get a picture, I studied its patterns and positioned the camera where it would likely pass or land, but there’s another catch: In this game, you turn the Playdate’s crank to rack your camera’s focus, which affects both birds and the environment. If you focus on the branch, will the bird that lands on it also be in focus? Perhaps, and perhaps not. Be patient, make a guess, and try again if it doesn’t work out.

The photographs that result may not be as detailed as the ones in other photography games, but the camera-work here is much more involved and interesting. Many of the photographs are a puzzle: how do you lure that bird in the reeds into plain sight? How do you take photographs of the bird in the dark cave? And is that even a bird? These puzzles extend out to the world as well: the town hosting the birding contest is full of lovable weirdos who chat in coffee shops, scale mountains, and hang out at the beach. Some of them are helpful, some want something from you, and some punch you in the stomach. To make it into the contest, you’ll not only have to work to understand the birds, but also these townspeople. I enjoyed getting to know all of them through our conflicts and conversations: they made me smile and laugh, and I appreciated every one of them, even if I hardly learned any of their actual names.

HYPER METEOR

Developed by Vertex Pop.

Here’s an odd thing about the Playdate’s crank: because it’s positioned on the right side of the device, it’s a bit awkward to turn the crank with one hand while hitting the face buttons with the other, since those buttons are also on the console’s right side. Fittingly, many crank-based games use the left-aligned D-Pad in place of face buttons, with its inputs corresponding to actions rather than directions. HYPER METEOR is one of those.

The premise is familiar, because the premise is Asteroids. You are a ship, simple and triangular, in the middle of a space increasingly crowded by floating rocks. Rotating the crank turns the ship, and pressing up on the D-Pad starts acceleration. Because the crank is sensitive to the speed at which you turn it, the ship is capable of hairpin turns less feasible or natural-feeling on an analogue stick. That motion is core to the game: you have no laser or gun like in Asteroids, only a bomb (triggered by pressing right on the D-Pad) to get out of hairy situations, and those are in limited supply. Your more reliable method of clearing debris from the field is ramming it, but there’s a catch. Every object in the environment has a white side and a black one: white sides are vulnerable to your collisions, but black sides are impervious, and you’ll explode against them on contact.

What results is a remix and inversion of a classic. Asteroids is a slow and defensive game: you pilot into open spaces in order to shoot from a distance. But HYPER METEOR is agile and aggressive. If you wait and evade, the field will become crowded and more dangerous. In order to clear the asteroids you have to get up close, orbit them to their vulnerable side, then turn inward and accelerate. And even then, they often split apart, putting you in the middle of shifting, dangerous bodies. It’s a nimble game, a game of quick pivots and accelerative bursts, made more dangerous as you play on and encounter genuine enemies with projectiles and targeting systems. It’s an old classic, translated through new technology, and made new itself. It does not become revolutionary, as it’s still bound by its forebear’s DNA, but it’s an admirable remix. For something more novel and risky, try Star Sled by Panic, a first party game that shares the control scheme but aims for adventure rather than survival.

Ratcheteer

Developed by Shaun Inman, Matthew Grimm, and Charlie Davis.

Ratcheteer, like Hyper Meteor, is another traditional experience on the Playdate, but this time emulating top-down action adventure games reminiscent of early Zelda titles, complete with dungeons, gadgets, and its own intriguing world to explore.

In the far future, a disaster has blotted out the sun and kicked off a world-wide ice age. Most of humanity has chosen to freeze itself in subterranean cryo colonies until the earth is habitable once more, but they periodically awaken to accept shifts working maintenance on the cryogenic systems. Your shift has now come, and it’s up to you to investigate a series of mysterious system failures threatening the colonies.

What makes Ratcheteer distinct from other Zelda-likes is its relationship with darkness. Outside the main town populated by your fellow maintenance workers, the dark caverns of the cryo colony aren’t lit, and you must carry a lantern at all times as you explore the underground wilderness. This lends the game its own unique character: though its world isn’t large, seeing it in small slivers of light changes your perception of it. I got lost, often, and wandering became the game’s core experience as I fumbled in the dark.

This wandering and prodding is characteristic of the game as a whole. Very little of the setting information I related earlier is told to you explicitly; instead, you piece it together from in-game records and history books. Among these texts are other pieces written in an alien language, which you have to decipher by finding translation glyphs scattered throughout the world. There is no deduction for the location of these glyphs: you simply have to explore. There’s a map to help, but it’s short on details, and mostly shows your position in relation to some key landmarks. When you’re in the dark, all you can do is piece together what you can see from your limited view. In Ratcheteer, to wander is to expand your comprehension.

Something I appreciate about games like Ratcheteer and Casual Birder, more than their skillful executions of classic genres, is there commitment to longer play experiences on a portable system. Many handheld games, whether on old systems like the Game Boy or modern devices like smartphones, skew for shorter play times and tighter game loops, “bite-sized” so you can play them in line, on the toilet, or in whatever other nook or cranny of time you find in your life. Think Angry Birds, Marvel Snap, or the new Fortnite mode designed to be played in five minutes. I don’t mind a short experience in a vacuum: Hyper Meteor falls into this category, as does Snak by stfj (another good Playdate title), and both of those games are suited just fine for either quick breaks or longer play sessions of multiple rounds. But when those games become the standard for a platform, what it communicates is a sense that those nooks and crannies in your days should be filled up, that your time should always be occupied. It disregards the empty space of our lives as wasted time, instead of time to just be a human in the world. I’m hoping the Playdate doesn’t become that, a toilet console or a stand-in-line console, that the Playdate is instead a platform for a wide range of experiences. Ratcheteer doesn’t revolutionize the action-adventure genre, but it does carve out the space for longer experiences, for getting lost, for wandering and wondering. It carves out a space for time well spent, and time to be human.

Spellcorked

Developed by Jada Gibbs, Nick Splendorr and Ryan Splendorr.

I’ve talked a lot about how the Playdate is defined by its hardware limits, but Spellcorked pushes up against a limit I hadn’t given much consideration: the console’s single menu button.

In Spellcorked, you play as a witch who has recently graduated from the “University of Witchery” and opened a potion shop in a small town. This goes against the advice of your professors, who think you would be more successful in the city, but they still reach out often to express their support. Every day you check your email for new orders, then you mix your brews and ship them out. The process is involved: after reading out orders on your computer that ask for desired magical effects such as “Strong Joy,” “Medium Armor,” or “Weak Sleep,” you consult your grimoire to determine which ingredients, prepared in which ways, will provide those effects. Then you go to your pantry to select your ingredients, and then you move to your workstation to mix the potion. But by the time I came to my workstation, after all those steps, I only had a fuzzy recollection of what kind of potion I was supposed to make, and how I was supposed to make it. The game doesn’t keep track of anything for you, and I ascribe that to the Playdate’s menu button.

Most modern game controllers have multiple menu buttons: one for accessing the device’s system menu, and one or two more for accessing in-game menus. So when playing Breath of the Wild on Switch, the plus button pauses the game to access your inventory, the minus button pauses the game to access your Sheikah Slate, and the home button pauses the game to access the Switch’s home screen. But on the Playdate, a single button both pauses the game and accesses system controls. Some games code extra functionality into this menu, but Spellcorked doesn’t, and has no other menu or feature for keeping track of your orders, ingredients or prep instructions. So how do you manage it all?

The answer is easy, obvious, and unnecessary in most modern games: you write it down. You take out a piece of paper, or your phone, and you write it down. You take notes on the order, you take notes from the grimoire, you grab your ingredients, and you move to your prep area. In this way, the game leaves the screen: the Playdate is a window into the game world, but you create the workstation in real life. You consult your real-world notes while picking out coffee beans or dewdrop berries or dragon scales. You hold the Playdate to turn the crank and mash the ingredients, referencing your notes to determine the right amount of pulverization. You even tilt the console to pour your brew into its vial and then label it for shipping. These are decorative uses of the Playdate’s crank and accelerometer, and that decoration helps reinforce the process of potion making as a physical act that you’re doing in the physical world.

SpellCorked is a simple game of simple, pleasurable labor. I enjoy its characters, its physicality, and its calm pace. When was the last time a game left the screen like that? For me, it was probably The Witness, which necessitated a pile of notes that cluttered my desk. Games like this can be a valuable reminder: it’s good when titles force us into this position of bringing the game outside of the screen. But it’s an option that is always available.

Crankin’s Time Travel Adventure

Developed by uvula.

Crankin’s Time Travel Adventure is a marquee title for the Playdate, and for good reason. Because as much as a system’s limits can imbue its games with character, so can its capabilities, and no other Season 1 game uses the Playdate’s crank in such a brilliant way.

You play as Crankin, a wind-up robot man who wakes on his couch late for a date with his ladyfriend Crankette. Crankin’s every step toward Crankette is pre-determined in each level; as a player, you control the time it takes for Crankin to reach her by turning the crank, which moves him along that pre-set path. Turning the crank faster moves Crankin faster, and leaving the crank in a single position renders Crankin motionless, even if he’s between steps and suspended in the air. Because what you’re controlling is not Crankin’s position in space, but his position in time. His forward movement is achieved by turning the crank “clockwise,” while “counterclockwise” rotation will send him walking backward to his couch. However, your control over time is limited to Crankin: a clock in the screen’s corner ticks ever forward, making Crankin ever later for his date. Despite your control over time, “on time,” isn’t an option, so you’ll have to settle for “minimally delayed.”

The game takes place across a series of dates, and Crankin wakes up late for each one of them. The first date is simple: just move Crankin forward through time until he reaches Crankette, who is displeased at his tardiness; you’ll have to try again tomorrow. For the second date, Crankin stops to bend over and smell a flower, but then continues to Crankette, who is once again displeased. For the third, Crankin encounters a field of flowers and stops to smell each one of them. A butterfly floats in this field, its movement situated in its own track of time unaffected by the crank’s rotation. If Crankin is standing or walking, the butterfly collides with his head and forces a reset of the level; to get past it, you have to navigate Crankin through time so that he’s bending over to smell a flower when the butterfly passes overhead.

In Time Travel Adventure, you cannot succeed only by moving forward, and you won’t get anywhere if you just retreat to your couch. You have to read the world around you, understand your situation, and act upon that understanding by using the crank. Sometimes this means moving forward, and sometimes it means moving back. Sometimes you have to move quickly, while other situations demand a slow pace and a cautious eye. All of this is needed as cycles repeat, as Crankin’s path to Crankette grows increasingly complex, and as Crankin becomes increasingly tormented by an assortment of butterflies, pigs, and storm clouds. There are mazes of staircases, birds that rocket out from the periphery, impossible situations, and an always-displeased lover. Crankin is trapped in time as a cycle: he has some latitude in how he navigates it, but the ending is inevitable.

The game is presented as a comedy, and it is very funny. Crankin moves with a toy’s squeaks and ticks, and these sounds get distorted in relation to the crank’s speed. The situations grow ever more absurd, and I feel for the guy as he wrestles with the unrelenting force of time and it’s still never enough. I feel for him because games don’t just reach out of a console and enter our world, as Spellcorked did for me: a good game allows us to bring our whole selves into its space, along with our experiences and thoughts, and draw meaning from the exchange. Crankin’s Time Travel Adventure is a silly game about time. But to me, playing it feels bittersweet. I, too, have been thinking about time.