Developed by Konami.

The nuclear weapons disposal facility on Alaska’s Shadow Moses Island has been taken over by terrorists. As U.S. secret agent Solid Snake, you have been dispatched to the facility to rescue hostages and stop the terrorists from making use of the nuclear refuse. Your handler is Colonel Campbell, who speaks to you over the radio-powered “codec” embedded in your ear. He gives missions updates, briefs you on your enemies, and advises counter-measures. And in his gruff, serious voice, he tells you, “when you want to use the codec, push the select button.”

There is a tension running through Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear Solid of balancing the human and the video game. What stands out to me about moments like these is that Campbell’s invocation of video game reality doesn’t diminish his humanity or seriousness. Yes, this is a video game, he implies, but there’s still a job to do. His fourth wall break doesn’t undercut his sincerity as is common in other works that use the technique, and Metal Gear Solid is an inherently sincere work. It is also a work of wild ambition clashing with good sense.

About halfway through Metal Gear Solid, you’re confronted by a sniper at the far end of a long hallway. None of your weapons can reach her, but you’re given a tip that you can find a sniper rifle of your own to fight back: you just have to backtrack through two twisty buildings, a field full of land mines, and a cave full of wolves. Once equipped, you then re-navigate through those same spaces, return to the same hallway where the sniper hasn’t moved, and have your shootout. But after all that, what follows is not an exciting duel: the controls for the sniper are touchy and unwieldy, making the long-delayed fight an exercise in frustration at the end of a pacing disaster.

Metal Gear Solid bills itself as “Tactical Espionage Action,” and it’s almost always the “Action” that gets it in trouble. This trend is established early on in a fight against “Revolver Ocelot,” and it’s a bizarre, off-key experience. He makes a big deal of himself and shows off his gun, “the greatest handgun ever made,” and then he’s a terrible shot, with most of his bullets going far wide of my position. But I’m a bad shot, too: the game is played from an overhead perspective not conducive to the action being asked of you, one which harshly limits your field of vision, and Ocelot often stands at the edge of that range. Our fight was clumsy and simple and dull: eventually, fewer of my shots missed than did his, and it was over. And most of the game’s action scenes follow a similar template, to similar results. These combat scenes feel obligatory, either as a concession to video game standards of action and excitement or as an evocation of the spy films that clearly serve as inspiration for this title. But they fail far more often than they succeed.

While the game’s combat scenes frequently weigh the experience down, they do help to contextualize the predominant stealth mechanics. And Metal Gear Solid is primarily a stealth game. In the top right corner of the screen is a radar that shows your position, the positions of your enemies, and your enemies’ fields of view. You can play a bulk of the game’s stealth sections by watching this screen: observe the enemies’ patterns, move into the gaps in their awareness, and move on toward your objective. In this sense, the game’s clunky combat is an asset, not an issue: Snake is relatively underpowered, which provides real threat to the prospect of getting caught. And when Snake is spotted, it’s often more advisable to retreat than to fight.

The stealth is simple but capable, and it’s through stealth that you explore the Shadow Moses compound and the game as a whole. The nuclear facility is varied: while it’s mostly painted in grays and washed out tones, the level layouts are diverse in structure and scale, and pocked with small stealth challenges and puzzles. Some of these puzzles have baffling solutions that may only occur naturally to the game’s designer, which is a hallmark of another genre, the point-and-click adventure game. In playing Metal Gear Solid I kept thinking that genre may have been a better fit for the story and scenario laid out here, to emphasize the clear strengths the game has in world-building and characterization. But either way, I’m fond of the unique solution Kojima implemented: whenever Snake is stuck, he can call his team of support specialists for advice. And I called them all the time.

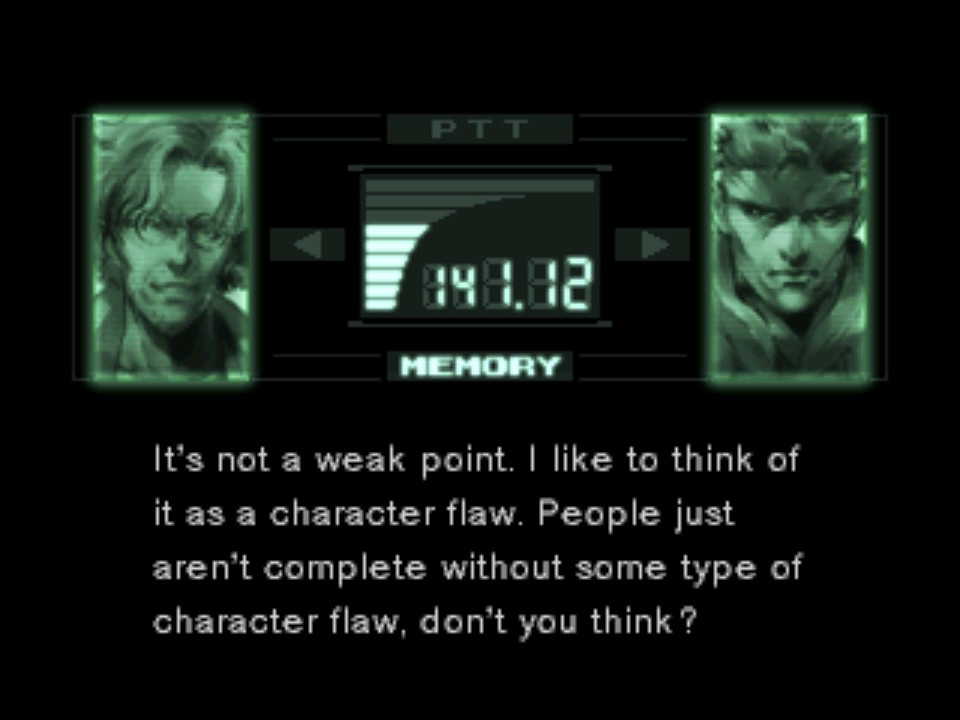

The characters of Metal Gear Solid are all, to use Seinfield parlance, “long talkers,” who will talk at length about their passions and obsessions. In another game this could have been annoying, but Kojima has imbued his characters with not just extended knowledge, but an enthusiasm for that knowledge paired with oddball quirks that make them charming and memorable. After all, what is more human and sincere than sharing something you love? Colonel Campbell is an old soldier who both wants the best for his country and is clear-eyed about the sacrifices that will require. A nuclear scientist with knowledge of the base asks you to call him by a goofy nickname that references his love of anime. Mei Ling mixes a heavy-handed obsession with proverbs and philosophy with a genuine sense of care when asking if you want to save your game. Curiously, Mei Ling, along with almost every other female character, expresses overt sexual interest in Solid Snake. How strange! The one exception is Meryl, the “Bond-girl” styled female lead who mixes ambition and vulnerability. Unlike the other women, she assures you romance is not an option, declaring, “[my military training] gave me psychotherapy to destroy my interest in men.” Anyway, her story has a twist at the end that you may not believe, but far be it from me to spoil that here.

As silly as that can sound, it’s through the characters and exploration of the setting that Kojima evokes compellingly human themes and narratives. Some of these are timeless, like anxieties of nuclear war, while others are prescient, like the nature of patriotism and concern around the roles left for masculine and competitive personalities in a changing society. Some themes are rather personal, too, mostly expressed by the game’s enemies who will also access your codec frequency to taunt and cajole you, but mostly to share their whole life stories and grievances. And while the resulting boss fights tend to drag, I almost always enjoyed talking to these jaded villains, except for the game’s main antagonist: everything he has to say is overlong, nonsensical, and irrelevant.

And it’s worth mentioning that there are exceptions to the bad boss fights. There’s a second sniper duel later on, this time in a dark snowfield. The mechanics are the same: calm your nerves, aim, and fire. But the feeling is different. Since it doesn’t come off the heels of excessive backtracking, I don’t feel hurried and irritable. The environment lends more interest and ambiance as well, with the darkness and the trees creating feelings of being isolated and exposed. And while the gameplay is logically the same as what came before, colored by this new context, it changes. It’s still not fun, but it is tense. It’s an embodying experience: the simple controls allow you to inhabit the feeling of being stranded and fighting for your life. You aren’t remarkable, you aren’t a typical video game action hero. You are a person, in a dark wood, with another person who wants you dead.

This is Metal Gear Solid at its best, embracing video game mechanics and conventions to make you feel human rather than super-human. It’s tempting to wish for a game that had this level of human embodiment across the board, but that’s not the one we got. Instead, we got a stealth game with unsuitable action ambitions. We got a game that is at times both human and un-relatable. We got a game that is both prescient and obsessed with nonsense. We got a game that is easy to poke holes in and yet, days after finishing, I feel my complaints melting away as I’m left with fond memories. The parts that were sincere, human, and unique left a deeper impression than the flaws. This is the most uneven game I’ve ever played. I can’t wait to start the next one.