Developed by Team D-13.

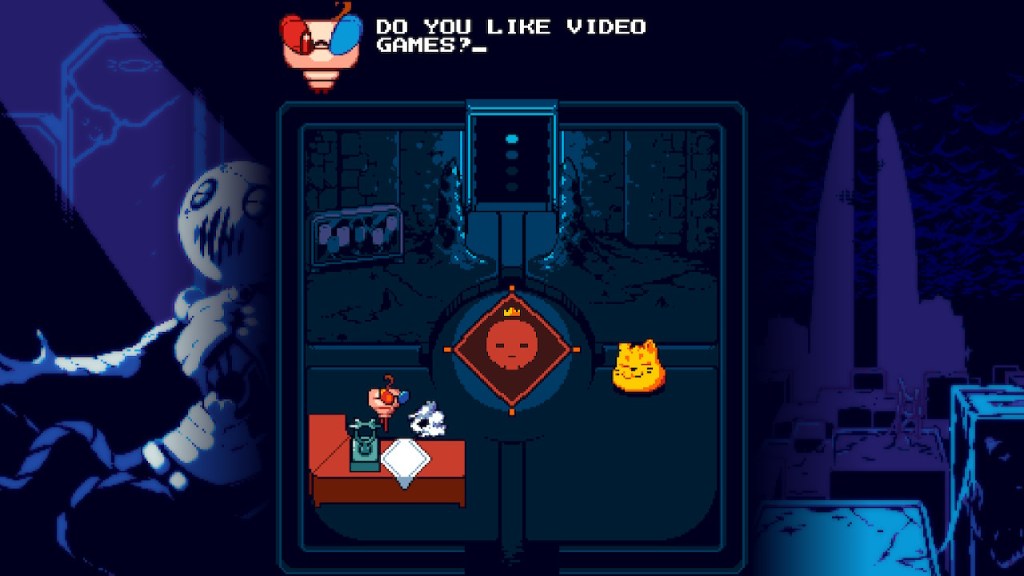

Star of Providence starts with a subterranean facility, a hole in the ground, at the bottom of which lies the “Power Eternal.” That’s what you’re told, anyway. What you’re not told is that this chasm also serves as a kind of collage-piece of video game history. There are shifting, roguelike labyrinths composed of Zelda-style dungeon rooms. There are enemies: the monsters, evil wizards, and machines you’ve seen and shot at in so many other virtual worlds. There’s even the occasional arcade cabinet, charging cash and dispensing prizes. And then there’s you: a spaceship, absent a pilot and pointed away from the stars and toward the deep earth. It’s strange, but what is not understood will not be explained: it will be discovered. The trick is to not mistake familiar sights for inherent meanings.

Star of Providence explains little up-front. There’s one tutorial that covers the very basics: move, shoot, dash, and drop bombs. This is familiar to me, the basic language of the twin-stick shooter, one of gaming’s oldest genres. And as I fight through the dark, I find that many of the lessons from those games hold up. Stand back from your enemy to better give you space to dodge their laser fire. But avoid the walls, which halve your ability to maneuver. Bombs wipe enemy shots off the screen, making them ideal getting out of tight spots. But then, something new. Sometimes your bombs knock out a nearby wall, revealing a space long sealed off, holding a prize, or maybe another enemy. In playing among the familiar, something new is discovered. And strategy can’t be taken for granted.

In a typical twin-stick shooter, where combat is the focus, bombs are used for defense, for those “tight spots” that are so common within enclosing patterns of bullets. But here, bombs are also used for exploration, becoming a limited resource that can be split in two ways. And while action games can lull you into a sense of instinct and autopilot, this contrast forces you out of it: instead of automatically using bombs for escape, can you fight harder, survive smarter, so that you don’t need them in combat, so that you can save them for exploration? And if you’re intending to save them, will you still allow yourself to use them in the moment, when you really need them, before it’s too late? And here’s the other rub: some bomb-breakable walls are marked with cracks, but some aren’t. How many bombs are you willing to use to test walls that may yield nothing? And with these mazes ever-changing, can you learn to predict where these secrets will be hidden?

Unexpectedly, Star of Providence has become my favorite archaeology game of the year, hiding so much unexplained strangeness beneath its familiarity. That floating skull that burps lasers at me? It’s a machine. How do I know? Because it’s weak to my anti-machine weaponry. Why was it built? Why does it look like a skull? I can only guess. This curiosity extends to the games systems, where better understanding is key to your survival. Learning to find secret rooms efficiently conserves more bombs for combat. Learning that I did not have to fully explore each floor was also key for me: just because those unexplored rooms may have rewards doesn’t mean I’ll survive their exploration. All of this must be intuited rather than taught, like holding a foreign object up to the light and inspecting it from multiple angles. When have I discovered enough, and when do I need to learn more? And when is my knowledge incomplete, or false?

Success here resists “turning your brain off,” resists “autopilot,” which is ironic for a game about a ship with no obvious human presence. At the same time, it’s simply not practical to actively “think” your way through a screen filled with deadly swirls of bullets and fire: some situations need to be managed instinctually, subconsciously. There is a tension between long-term planning and in-moment instinct, two different and interconnected parts of living, and it was between those two points that I had to make the most challenging decisions.

Part of each run is discovering and upgrading your weapons, an always-active balance of risk and experience. On one run, I built a triple-firing, high-damage homing laser, and got farther than I ever had. I spent the next dozen or so runs trying to re-create it, and never succeeded. Ultimately, I had discovered just one successful strategy: what would push me out of repetition and toward growth was experimenting, and doing something new. I made many new weapons by combining their modular qualities; they were often strange and nonfunctional, but these were weapons that taught me many different things. Some of those lessons were about game elements: homing and ricochet qualities are often redundant. Weapons that target a specific enemy type mark them with a kind of red halo. But other lessons pointed the magnifying glass back at me, challenging me to better understand myself as an agent in these systems. I benefit from homing weapons because moving and aiming is too much cognitive load for me. I avoid weapons that need to be charged, that’s also too much to consider in a firefight. And while I want to prioritize qualities that will be helpful in fighting bosses, tailoring a weapon for smaller mobs often means I arrive at the boss with more health anyway. The problems before you can be understood in multiple ways. The solutions are grounded in both an understanding of the game, and of yourself.

As I keep playing, keep getting deeper, I will remember these lessons and become stronger for them. But I will not take them for granted. This labyrinth is always shifting and changing, and what I think I know can be challenged by what I encounter. I’m changing, too. What’s true of me today may look different in tomorrow’s light, or in its absence.