Developed by Megagon Industries.

When I went skiing for the first time in over a decade, I fell constantly. I fell on the slopes, and I fell on the flats. I fell exclusively at low speeds, because I never made it up to high speeds. There exist many photos of me face-down in the snow. I was so rusty, but I used to be good at this! Anyway, even that was some time ago. More recently I picked up an alpine skiing game for my computer; the results were similar.

I played Lonely Mountains: Snow Riders for a day and fell constantly. For reference, this is a game where you pick a voice when you design your character, but you only hear that voice as a grunt or scream as they slam against a boulder or sail off a cliff. There is an expectation of death, if not a familiarity with it, and I died many times on that first day. But then a week went by where I was busy, and then the busyness stopped and I started playing again. To my surprise, I was now surviving much more reliably. I was smoothly navigating corners, halting before cliff ledges, and following both the gentle and sharp curves of the mountain. It’s not often that time away from an activity will improve your skill; what happened?

During my break, I had forgotten that you go faster by holding down the “A” button to lean forward. That’s what happened. I had improved because I had forgotten how to be reckless.

Snow Riders is both a tough teacher and a lethal wilderness. It starts with a simple tutorial, and then drops you on a series of mountains with little guidance save the obvious: get to the bottom. The tutorial is kind and sufficient in teaching the very basics of turning and acceleration, but then you have to reckon with the mountains themselves, and these mountains are trying to kill you. Still, there is a kindness to it.

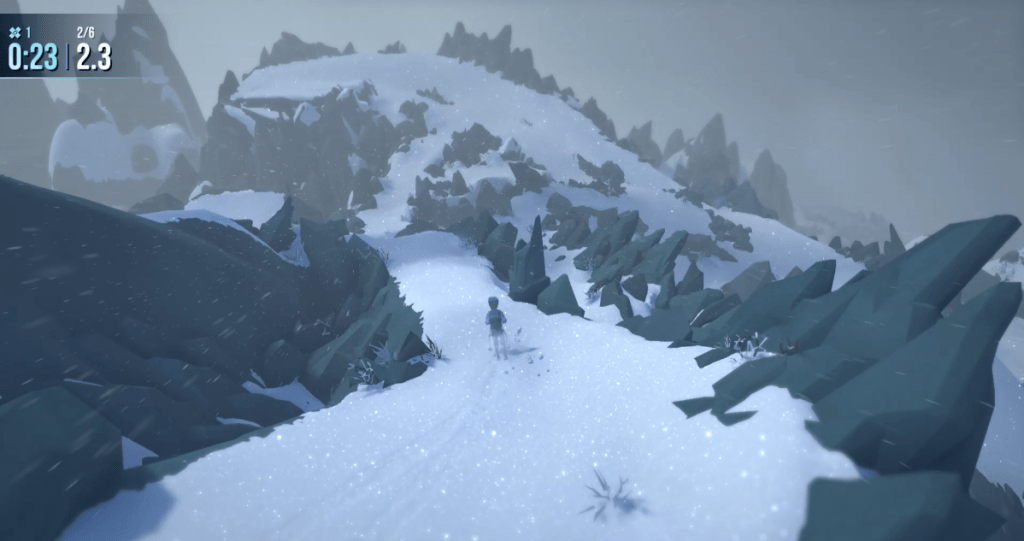

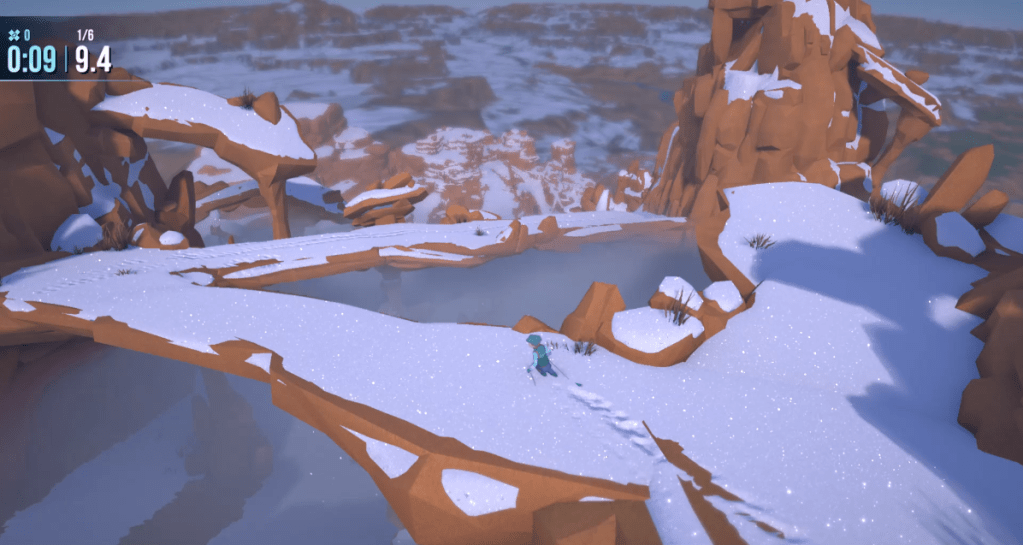

Wide paths that allow for acceleration are dotted with jutting boulders. Frozen creeks are too slick for proper control and terminate in empty air above canyons. Mountaintop crowns made of black rocks dare you to jump from this snowy patch to that. Uneven paths lace between trees, overlapping and contorting. This land is unmoving and unyielding: your skier is the lone source of real motion, aside from the snow sprays of your skis and occasional skittering pebbles. Birdsong is heard, but birds themselves are never seen. Movement is risk and taboo, and also your reason for being.

You break the law of stillness as you ski, and every tree and boulder and ledge is an officer waiting to break your neck. The unyielding environment isn’t just the stone and ice and flora, it’s also the camera, always locking you into a predetermined point of view. This frames the mountain beautifully, zooming out for large hills and vistas and pulling in for tight spaces. But it also conceals. It conceals the deadly rocks and stops and edges, it fools and lulls, it makes you think now is the time to pour on the speed and leaves you to consider your errors after your latest scream and crunch.

Death is an abrupt teacher here, but also a reasonable one. There is no guidance except consequence. With every final scream, you are restored to the nearest checkpoint. Your previous attempts remain as tracks pressed into the snow. They are the only guides you have, and they’ve killed you once already.

How do you learn? You move, and then you move differently. Forgetting about the “A” button’s acceleration taught me that the game’s highest speeds were more situational than I had believed. When I collided with trees, that was a warning. Incorrect movement is promptly punished, but skiing with consideration leaves only one set of tracks on the mountainside.

These mountains have branching trails but few discrete secrets. The more difficult trail is not always the fastest, and the fastest is not always the most enjoyable. Your path down doesn’t even have to depend on trails, not when you can descend a series of snow-topped boulders, or when you stumble through gaps in the trees. There are ways to fall that fit into your motion and provide a smooth landing instead of dashing you upon the rocks. There is the path of the trail and the direction of the camera, and the two are not always aligned. There are no animals, not ever. And there are jumps that are both tempting and unwise. These levels contort themselves into shapes and configurations unseen in nature, including looping stones, crisscrossing natural bridges, and cacti on snowy mountainsides. And yet, they don’t feel constructed. I didn’t feel an intentional hand pointing to a correct path, just a space to explore and understand. Understanding is both the survival strategy and the reward.

And there is more to dig into. Changing skis changes your relation to the landscape. The viper turns easily, allowing for a side-winding descent. The cheetah plummets quickly, and needs to be balanced with intentional braking. But if you’re constantly braking? It’s a dull descent and an unattractive track to leave behind. Don’t do it, it isn’t worth it. There are jumps too, and tricks you can pull out when airborne. I didn’t bother; I may not be humble, but when my motion was steady I didn’t want to risk it more than I had to.

There’s multiplayer too, the game’s lone opportunity to learn from others. It doesn’t make the mountains any less lonely, though, because crashes and timidity can leave you far behind your peers. Anyway, the true loneliness comes from the lack of instruction, the sensation of being the sole source of motion in still lands. But that feeling isn’t abandonment, it’s trust. And trust is always a kindness.