A man cowers in a dark room. All surfaces are metal, periodically lit by green text scrolling on a black monitor. He has no weapon; the last gun was held by his companion, who is in pieces on the floor. Opposite the man, dripping blood but otherwise still, is the beast. It has no beginning and no end, just a tangled mass of ruptured body tissue. Eyes and sets of gnashing teeth dot its body at irregular intervals. A tendril rises slowly from its shuddering form; it waves in the air, purpose unknown.

This scene would be typical for any horror movie, but Carrion is a subversion of common expectations. In this game, you play as the amorphous, unknowable beast, and the computer plays as the fleeing victims. Both roles present challenges for their respective actors, and while the scene isn’t perfect, something novel is born from the experiment.

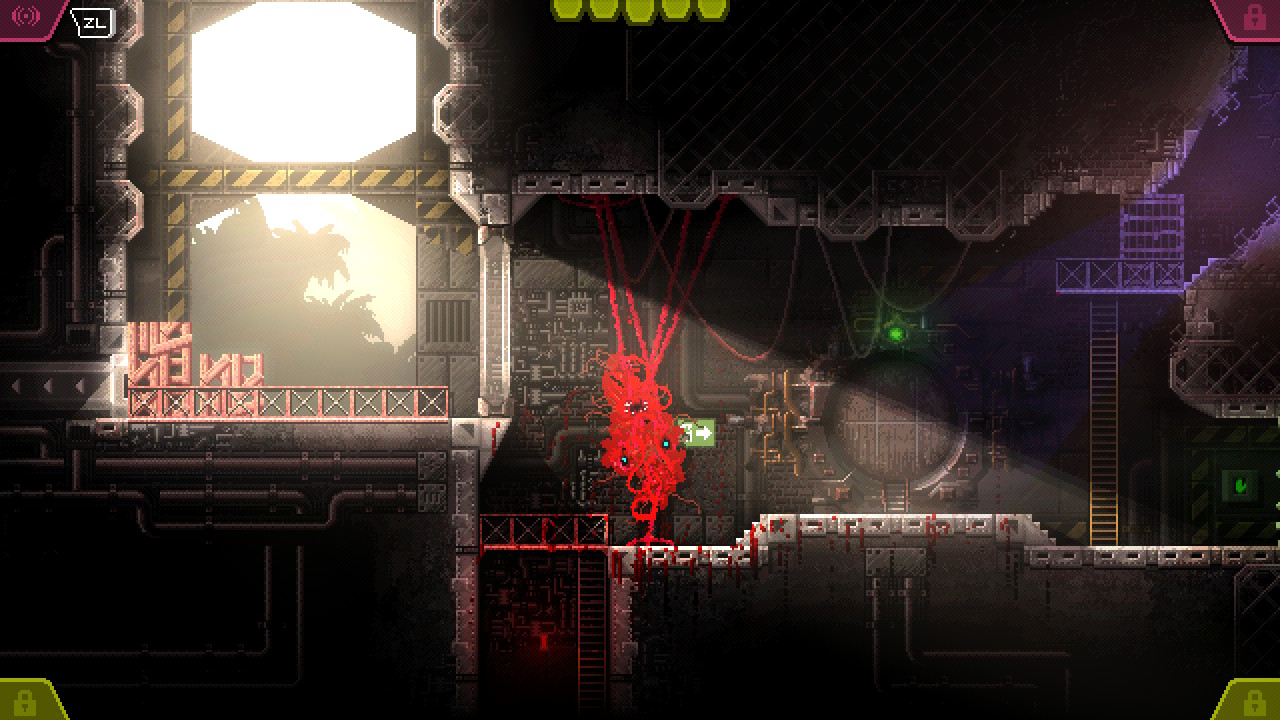

As a playable character, Carrion’s beast is unique. When it first escapes its containment canister at the game’s outset, it looks like a clump of bleeding flesh. The game’s first surprise is that this wretched thing is rather nimble and spider-like. It can leap in any direction, extending red tendrils to anchor itself to walls and floors, and it does so with surprising speed. My first movements with the character were clumsy; I wasn’t expecting such speed from a clump of exposed body tissue, and I left red smears on each wall I collided with in the game’s first few chambers. And also every chamber after that: playing the game can be a bit like painting a sterile government lab with blood.

The narrative here is light, and the goal is presumed: escape. Upon leaving your containment unit, you find yourself in a maze-like research facility of metal corridors and scientific labs. The purpose of the facility is both not-known and not relevant; the whole place is locked down, meaning it’s merely another cage for you to circumvent. This gives the game a natural Metroidvania structure: search each area for any viable opening, whether an air vent or water duct, and use every means available to breach the locked doors in search of a true exit. Sometimes this means slipping into a control room to override lockdown commands. Other times you find radioactive substances that will augment your abilities, letting you slam through wooden barricades or activate a camouflage that fools laser tripwires. These new powers let you open up passages previously inaccessible to you as you further explore and dominate the compound.

The abilities you pick up are useful for unsealing the facility’s many doors, but they’re also integral to the game’s action sequences. Many of the facility’s rooms are inhabited by scientists and armed guards. Dispatching them is often straightforward: grab them with a slick tendril and drag them toward the beast’s teeth-covered mass. Devouring humans increases the beast’s bulk and changes its move-set, as different abilities are tied to the creature’s different sizes. The smallest version of the monster is lithe, and can trap prey in long-range webbing. Consume enough bodies and you become a multi-car train of body horror, not a single being but many clusters of flesh and teeth tied together with dripping sinews. You have no front or back, and both movement and attack erupt from whichever clump is nearest to your target. At this level, you become capable of filling rooms with volleys of rigid keratin harpoons, but even then you’re not invulnerable. Armed humans and security drones can shear off chunks of the monster’s flesh with bullets, or burn it away with fire. Between consumption and the onslaught of enemy attacks, your form and move-set is subject to change in combat, necessitating rapid adaptation.

I played cautiously in the game’s early hours, sneaking around foes and only ever attacking when safety was assured. It was effective, but not very engaging. Enemies move in regular patterns, and attack in predictable formations. Sure, the premise and mechanics were unusual, but playing in this way made Carrion feel like a standard Metroidvania merely coated in a horror aesthetic. It is a Metroidvania, and it is coated in horror, but that doesn’t mean playing to survive is the only form of play available. And certainly, that kind of behavior doesn’t actually drive most classic horror movies. Famous masked men with knives and monsters with teeth don’t just hunt and kill. They torment, deceive, and do the unexpected. I found the same can be applied here.

I began to experiment. I chased people into rooms that only had one door, then grabbed them from unseen vents. I dropped half-eaten bodies from the rafters onto their still-living colleagues. Upon gaining a possession ability, I took control of one scientist who would enter a room full of his peers, only to open the opposite door and causally reveal the bleeding, pulsing beast behind it. Grim, right? But playing is acting, and this game presents a unique opportunity for a new role. Once I reframed my perspective on the game’s action scenes from combat to torment, I found something more valuable in the experience.

Unfortunately, the game’s humans lack a proportionate sense of expression. They cower, run, and scream. All very reasonable, but they never show inventiveness or individuality in their reactions, and it seldom feels like you’re trapped in this complex with actual people. Further, there’s no sense of ongoing characterization. Horror movies are rife with disposable characters who are introduced and dispatched in the same scene, but the most thrilling chases are the ones with characters that the audience has followed for the whole film. There’s no kind of commensurate relationship-building here; each human only ever exists in the room they are found in, and they’re all indistinguishable from their fellows.

The game’s environments also lack distinctive personality. Different areas have different palettes and titles, but they all run together. Individual rooms are difficult to distinguish from one another, and early on I felt I would surely become lost. Luckily, the game provides you with a monstrous growl that indicates where prey is hiding; always go in that direction.

Something curious happens as you explore these drab hallways. Special cracks in the wall, or sometimes mysterious vents, allow you to infuse some of your horrific being into the facility itself. Dripping red flesh coats and corrodes the wall, breaking open passageways and extending tendrils to wrench open sealed airlocks. As the game progressed, I got the feeling that the beast’s being was not confined to the body I was controlling, but was spreading outward, changing the normal into the bizarre. The game structure here may be typical, but you have the opportunity to make something different. You explore, you hunt, you turn yourself inside-out.

Carrion is a specimen pieced together from the DNA of Metroidvania and horror stories to make something new. It’s not enough to be cast as the monster, though. To get the best out of this experience, you have to lean into the role, and become something strange and unknown.

Played on Nintendo Switch for review. Completed in under ten hours.