Developed by Nino van Hooff & Julie Bjørnskov for Playdate’s Season 2.

Absurdity is fertile ground for new gameplay. We take for granted the absurdity of Mario games: we’ve stomped enough goombas and collected enough fire flowers that the power-ups and obliterations seem not only logical to us, but typical. The same goes for many other video game conventions, such as the double jump or the health pack that revitalizes you in an instant. But when a game introduces something new, that’s when we pause and ask, “OK, but does this make sense?” We only question absurdity when it’s unfamiliar.

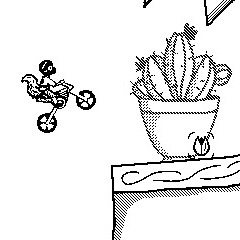

Wheelsprung is both absurd and unfamiliar, but only to a point. It’s Catalogue page advertises it as using “Playdate’s first full physics simulation,” which in execution means that this is the kind of physics-based vehicle platformer that is typical on mobile app stores and in web games. But while the genre is familiar, the setting itself is quite odd: you play as a squirrel, who is hunting for nuts in a family’s house. And to navigate this house, you jump on a small, squirrel-sized dirt bike.

To understand this game, you have to understand the dirt bike, how it rides and how it works. Holding down the A-button causes the bike’s rear wheel to accelerate, but with far more force than you would expect, pushing that rear wheel forward and lifting the front one into the air. If you keep accelerating like that, the front wheel will flip fully overhead and around to the back, sending the rider crashing off of the bike. To compensate, you have to lean forward or backward using the D-pad, and the right amount of lean depends on the situation. If you just want to bring your front wheel down to the ground, you lean forward. But if you’ve ramped off an object and into the air, you need to lean in such a way that your wheels will catch appropriately on whatever surface is least likely to kill you. This is difficult, because you are very easy to kill.

Important to this system is the squirrel’s head, encased in a black helmet. If the helmet offers any protective qualities, I couldn’t discern it in my playthrough: almost any amount of contact between the helmet and any surface will destroy the bike and force a restart of the level. It’s as if the helmet contains the bike’s self-destruct button instead of a skull, which pairs a clear sense of goal and risk to each level: collect nuts and protect your head as you make your way through the house.

The house you have to navigate on your dirt bike is rendered like a child’s drawings, in swooping scrawls of thick marker across unevenly abstracted objects and rooms. A bath area suspends its pipes in mid-air, spitting out frothy water that houses submarines and fish. A bookshelf is annihilated and unraveled into a roller-coaster surrounded by monsters, fairies, and hot-air balloons. I wonder from whose perspective this game really plays out. Is it the squirrel, too concussed from his time on the bike? Or is it a child, imagining the whole thing?

But as much as I appreciate the abstraction of this world and premise, I keep coming back to the core gameplay, which is a lot like many other vehicle physics games, and I’ve never liked those much. The bike requires a lot of monitoring to drive effectively, but the courses confine you into spaces and tracks that feel designed to slam you into walls and start the levels over. In this sense, each level is a puzzle: how do you get through and not die? But it’s a puzzle where understanding of the general principle often happens far ahead of nailing execution, which can only be teased out through a lot of touchy trial and error. The bike allows for a lot of fine control, and these levels demand a high level of precision to surmount. But often, the required precision has to happen in tight time frames, in split-seconds before your head collides with a wall that’s only just become visible. Fine control in an open space can feel pleasing to master, but fine control in a demanding one can just feel fussy and fragile.

I appreciate that Wheelsprung utilizes the Playdate’s first full physics system to create what is possible on other platforms. But vehicle physics games on other platforms were never particularly inspiring, and the genre’s transition to the Playdate hasn’t made it more so. I appreciate the game’s absurd worlds, but I wish it had taken a more novel approach to its actual play as well. This game is absurd, but it’s also not anything new.