Developed by Jump Over The Age.

It started off bad. On the run from my former master, I had pushed myself too hard scrounging up money to put distance between myself and my pursuer. Stress piled on stress, systems failed, and then a flash: I died in the freewheeling vacuum of space. And then I woke up.

Citizen Sleeper 2: Starward Vector is a text-based science fiction roleplaying game set in a distant stretch of space called the Hellion System. You play as a “Sleeper,” an android imprinted with the personality of a human and built for labor. You’ve just escaped your employer/owner, Laine, and now you’re on the run. Paradoxically, your escape into “freedom” has led you into more work, as escaping servitude does not mean escaping capitalism. In order to make ends meet and put distance between yourself and Laine, you and your crew of interstellar vagabonds must bounce from station to station in the Hellion system, scrounging up connections and taking on the only work available to fugitives: the dangerous kind.

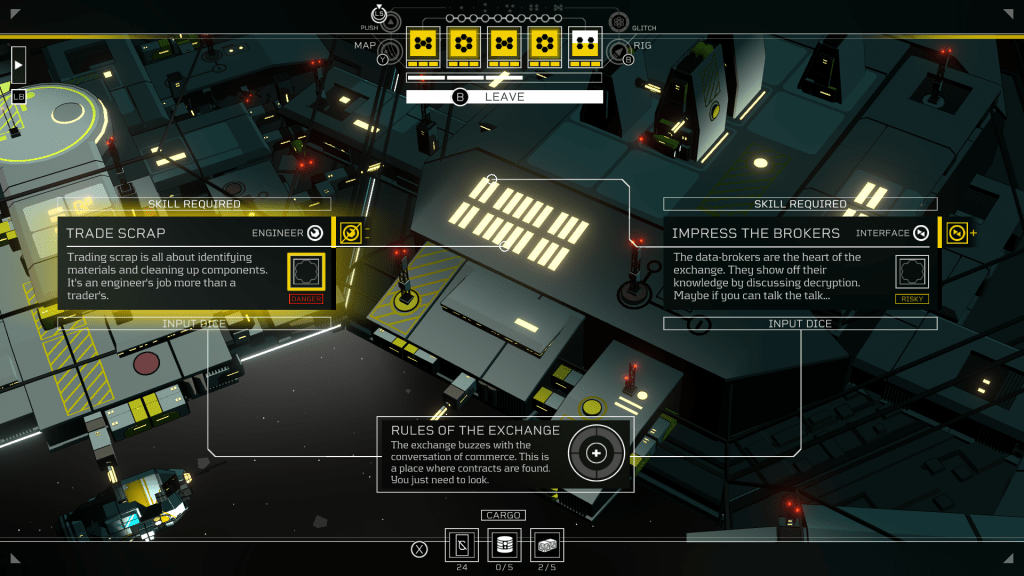

The game is split into two alternating phases: hubs and contracts. Hubs are space stations where you can take on odd jobs for petty cash, network with contacts, and restock on fuel and supplies. Contracts are dangerous missions of dubious legality, like recovering valuables from a wrecked spacecraft or spelunking through the bunker of a long-dead corporation. And to make the most of the hubs and contracts, you’ll need your skills and your dice.

All tasks in Citizen Sleeper 2 are dice-based. You wake up every cycle (roughly equivalent to a day, but those don’t exist in space), roll five six-sided dice, check the results, and roughly know whether you’re in for a good cycle or a bad one. On a hub, you might be helping to harvest plants in microgravity, or hacking into a terminal to download a station map. On a contract, you’re more likely to be breaking through ancient security doors, or drilling into an ice-coated asteroid. Each of these tasks cost one die to engage in: put a six-die in for a guaranteed success, but a one-die will have a great chance of failure and negative consequence. Your Sleeper’s skills can tweak the odds: my Sleeper specialized in programming, so all programming tasks treated my dice as a number higher than it actually was, while endurance tasks diminished my die’s potency.

Complicating things is the fact that almost every contract or story objective takes multiple cycles to achieve: you can skip using your low-numbered dice to avoid negative consequences and hope for a luckier pool on the next cycle, but doing so means running the risk of depleting your limited supplies and starving to death. But pushing ahead with low-numbered dice risks accumulating stress and damaging your android body, or even setting off security alarms and botching the contract entirely. The former happened to me, rather early in the game, too. I didn’t understand the game’s systems well enough, didn’t understand the odds, and kept pushing for an outcome that got farther out of reach with each failure. In doing so, my robot body shut down entirely, unable to sustain consciousness. And when I awoke, there was a consequence: my body had developed a permanent glitch, all but guaranteeing that one of my dice would be useless every cycle. I was permanently hampered in an already unfair universe, and my journey was just getting started.

As a game system, the dice and contracts evoke a sense of cosmic unfairness and random chance. If you don’t take on dangerous contracts, then your only way to earn credits is by taking on odd jobs around the stations, which pay poorly and won’t buy the fuel you need to outrun Laine. If you do the contracts, you risk a run of bad dice rolls and damage to your body. This fuels a wonderful tension with the game’s narrative: regardless of whether you aim to be a saint or a survivor, you’re constrained by your resources and luck. It adds weight to the game’s meaningful narrative decisions: do you trust the person who already screwed you over, knowing they had good reason to do so? Do you take a risk looking for a rumored treasure, knowing that others may have beaten you to the punch years ago?

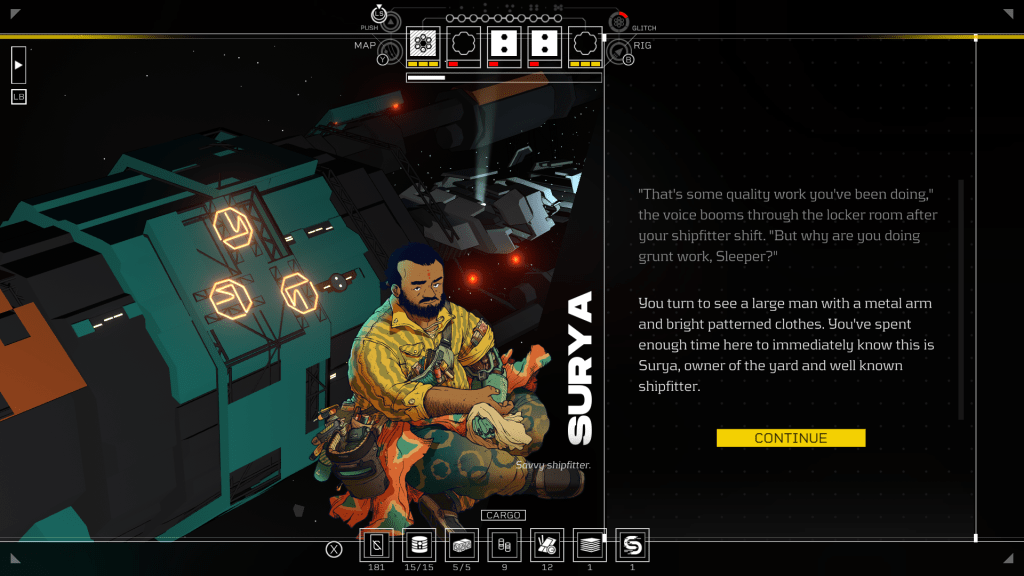

The game is at its best when you have to make these choices that, through narrative consequence and resource constraints, force a compromised decision. And for just over half the game, that was my experience. I bonded with my crew, and we burned across the void. We jumped from station to station, we suffered loss, and we made more strategic bets. Then slowly, over time, we stabilized. I grew to understand the game’s systems, better calculate the odds. And with each success, we earned both credits and experience to invest in skills. My sleeper strengthened their programming skill, and developed other supporting skills as well. And then, there was a shift.

At some point, I noticed that I didn’t need to make compromises anymore. I usually had a surplus of fuel, supplies, and credits. Instead of making tough choices I was now making optimal ones. I had braced myself to resolve fights amongst the crew, but with abundance I could make everyone happy. And I liked that, to a degree: the game is gorgeously written, from dialogue to descriptions to encounters. I loved spending time with these characters, loved drifting through space with them. But absent in the game’s back half was scarcity’s tension. I didn’t feel waves buffeting this ship: it was all clear stretches of space, and the free choice of where to go. It was pleasant, but it stopped feeling consequential and dangerous, even as the narration suggested otherwise.

As my character strengthened and my resources grew, close reading and understanding felt less necessary. I would head out on contracts and blow through all challenges. Beauty was present, but risk was gone. I didn’t even have to read the dice prompts, especially when so many of them would upgrade my dice to a near-total success rate. Even my permanent glitch got wiped off the board: I didn’t even ask for that, it just happened, an unsolicited reward for good behavior.

Part of this growth was certainly due to strings of lucky rolls, but also, the law of averages evens out over time and I dealt with my share of bad cycles as well. I think it mostly came down to the upgrade system: I was able to optimize my character in such a way as to render the challenges trivial. And sure, there are ways around that: I could have upgraded the difficulty (I played at the developer-intended “Risky” difficulty) or I could have declined to use my upgrade points. But those are choices that run counter to the experience I found valuable in the first place, one of carefully allocating one’s irregular resources because it matters. I don’t want to jettison my strengths out into the vacuum of space. The inclination to choose risk when you don’t have to runs counter to the inclination to survive.

In the end, I’m thankful for my journey, for the time I spent with my crew. They challenged my thinking and showed me a dark space pinpricked with surprising light. But the transition from survival run to brisk walk was jarring, and I find myself looking back, and thinking of what could have been.

Stray Thoughts

—You can avoid power-creep by declining side-quests, but I wanted to do the side-quests. They were often meaningful to my crew, and I liked the crew a lot.

—I’ve seen others draw comparisons to Cowboy Bebop, which is apt, but I’d like to note a difference in the music. Cowboy Bebop’s jazz was energetic in its action and wistful in the series’ quieter moments. Citizen Sleeper 2’s music is ambient electronica, and it often emphasizes a single, strange instrument among undifferentiated abstract sounds, like a lone whale breaching the surface of a cold sea. Both are well-tailored to their respective works.

—While the late-game power-creep is disappointing, Citizen Sleeper 2 has one of the most poignant post-game experiences I’ve ever played.