There is a dark room with a sandy floor far beneath the surface of Gizeh. I entered with a torch to push back the shadows, and found that it wasn’t needed: a pressure plate before me, when depressed, would open up a kind of skylight to leak in desert sun. There were several others, each creating small pillars of illumination at a touch: the room remained oppressively still, but now there was light, passing through airborne dust and landing on piles of dirty coins resting in the sand. Shadows pooled in the corners, but at the far end of the room was a statue holding the relic I sought. I just needed to overcome two kinds of dread.

The first was a dread of eeriness, of atmosphere and narrative. Indiana Jones has a track record of exploring and surviving places long dead, but stepping into his shoes didn’t alleviate my own human unease. Shadows conceal, and no amount of torches or skylights would banish them all. The room still held so much of the unknown, so much muted threat. And I didn’t think I could hold this relic for more than a moment without a fight: the ceremonial clubs littering the floor weren’t there on accident.

That was the second dread, a dread of the fight, but it wasn’t rooted in potential failure or death. Rather, it was just weariness. The combat in this game is dull and trying and repetitive: it can always be overcome, but never feels worth doing.

Indiana Jones and the Great Circle is many things. It’s a rousing adventure story that fits right into the character’s existing mythos. It’s a series of open world scenarios where you, as Jones, can travel the world and experience different cultures as they existed in the 1930s. And when you dive into tombs and crypts and old sites either long concealed or forgotten for centuries, it’s an evocative mystery, a spooky stalking through the dark. But too often, it’s stealth and combat. And neither one of them is very good.

Back in the room of shadows, I approached the statue, picked up the relic, and was immediately knocked off my feet. A giant of a man, eyes covered with ceremonial cloth and speaking a dead language, had materialized from the darkness to stop me. The skylights sealed as I was trapped in the same darkness that must make his every day. Save for my torch, that is: it still burned on the floor where it had been knocked from my grip.

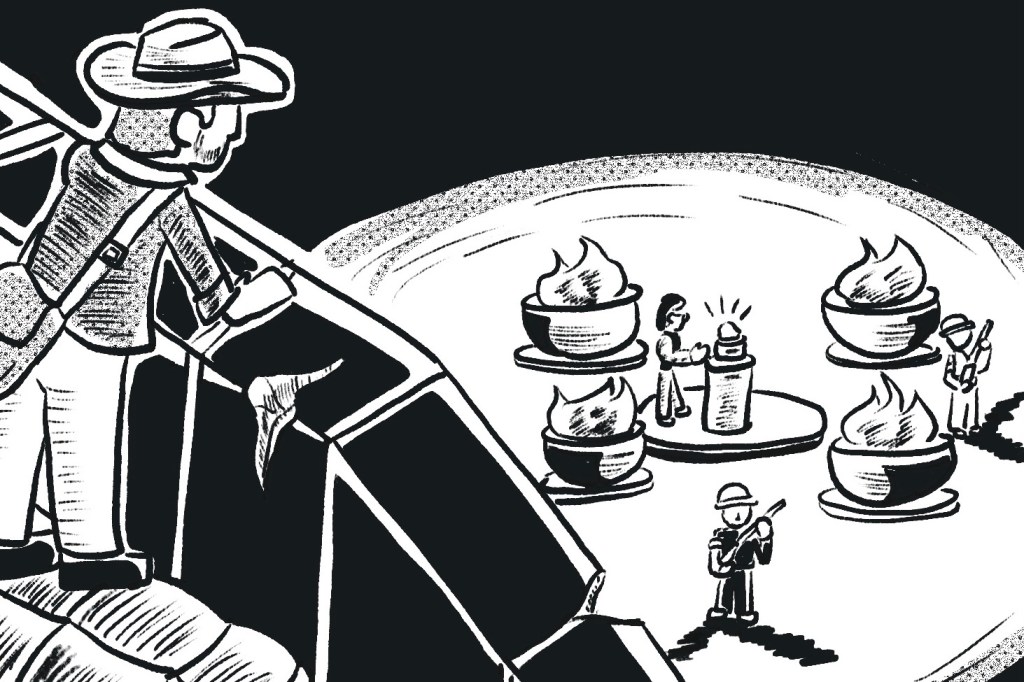

I picked up the torch and circled the room’s perimeter. The giant wouldn’t hear my torch’s crackle: the game had taught me on multiple occasions that most enemies, even on high alert, seem oblivious to the noise of anything you’re holding. When sneaking up on Nazis, you can knock them out instantly from behind using any held object, whether a bottle (smash!) or shovel (clang!) or violin (bwong!) and their allies, no matter how close, will never hear the strike. This is stealth: sneak up behind enemies and club them. If someone’s looking in your direction, throw some garbage to distract them. It works every time and feels like a job: did these enemies punch-in too, just to get punched?

So I held my torch, knowing that neither its glow nor its sound would betray me, and circled back to the pressure plates, re-opening the skylights. The giant could hear the plates, though: I scurried off of each one after activation. I still felt those dreads, but I was safe. And I could now see him.

With the room illuminated, I advanced on the giant. He would occasionally lunge through the shadows, scattering the coin piles loudly as he did so: no doubt those sounds would draw his attention if I did the same, but they were easily avoided.

Next up was combat. This man was large, and strong, but I had practiced my fists on many nazis and fascists over my time in the game, and I had learned the strategy: punch punch punch, your stamina meter has run out, walk away until it refills, and then punch punch punch.

I get it: Indiana Jones is not a martial artist. He is not a savant. He’s a college professor who longs for adventure, but then breaks from the rest of us by going out and finding it. The combat here is true to his character, straightforward and brash. But did it have to be so dull? So rudimentary? The first boss in the game I outlasted purely because he was slow. Punch punch, back up while he lurches after me, punch punch. It was effective, and it took forever. The same strategy worked here, too. I beat the giant in the dark. All it took was patience, and minutes of the one life I’ll ever live.

And this is a shame, because there’s so much here in the game that works. The characters are endearing! Troy Baker does more than justice to the classic Harrison Ford character! You tour a world on the brink of our most infamous war! There’s even a clever analysis of Nazi ideology’s inherently malicious ignorance and insecurity, which feels timely given the rise of fascism in our actual world.

But the core of the gameplay, the combat and stealth, are both irreparably dull. They are not made more interesting by increasing the (thankfully granular) difficulty. Instead, you’re best off dialing the action difficulty down to a minimum. You’ll still have to sneak, and you’ll still have to punch, but at least it won’t take as long. It reduces the dread of drudgery and allows you to focus on the dread actually worth the expedition.

Developed by MachineGames and published by Bethesda Softworks.